If 2025 was the year everyone demoed agents, 2026 is when we find out what happens when agents move from “cool sidebar” to “this is how the product works.”

The speed of progress is still kind of absurd. But the bigger story isn’t “chatbots got faster.” It’s that a lot of software is about to be rebuilt around a different assumption: the primary operator won’t always be a human clicking buttons. It’ll be an agent.

Here are the shifts I expect to matter most in 2026 (pulled from the same conversations you’re probably seeing too, including the Every crowd).

1) Agent-native architecture (finally)

We’re exiting the “paste a chat box onto the UI” phase.

Agent-native apps treat agents as real actors inside the system. Not mascots. Not assistants that can only suggest things. Actors with permissions, identity, and a clear way to do work.

A useful way to think about it is three layers of parity:

- User parity: if a human can do it in the product (change settings, update a profile, run a report), an agent can do it too.

- System parity: if internal code can trigger it (kick off a workflow, regenerate a brief, run a backend job), an agent can trigger it without being babysat.

- Developer parity: if a developer can do it (open a PR, fix a bug, update a test, ship a patch), the agent can do at least part of it with real outputs, not just suggestions.

You can already see hints of this in tools like Claude, Notion’s AI features, and a lot of internal “agent + permissions” work happening quietly inside companies. By late 2026, this won’t be a novelty. It’ll be table stakes.

The UX implication is simple: less clicking, more intent. People won’t learn your interface the way they do today. They’ll say “fix the settings” or “set this up for the new region,” and the agent will navigate the product the way power users used to.

2) The rise of the compound engineer

“Software engineer” is getting split into different jobs. Not because titles change, but because the day-to-day looks completely different depending on how you use AI.

I see three archetypes:

-

The traditionalist

Writes code the old way. Minimal AI usage. Still strong in many environments, but the “default” market for this style shrinks as tools get better. -

The AI-augmented traditionalist

Uses Cursor/Copilot to go faster, but still thinks of the job as “I write code, AI helps.” -

The agentic (compound) engineer

This is the breakout role.

Compound engineers don’t obsess over every line. They run an engine. They orchestrate agents, design constraints, verify outputs, and keep the system pointed at the right target.

It’s less “write code all day” and more “design the approach, set up the guardrails, delegate work, review diffs, iterate.” One good compound engineer can ship what used to take a small team, mainly because the throughput bottleneck moves from typing to judgment.

And yes: judgment becomes the job.

3) Designers become builders (for real, not as a slogan)

The handoff has always been the painful moment: designer finishes the vision, then it enters a different world where tradeoffs, interpretation, and compromises pile up.

That gap narrows in 2026.

As code gets cheaper, the people with taste get more leverage. Great designers and creative directors won’t just hand over Figma files. They’ll ship working product slices themselves, especially for UI-heavy apps where “feel” matters.

This is the part that’s exciting and slightly scary. The winners won’t necessarily be the people who can write the cleanest abstractions. The winners will be the people who can make something users instantly want to use.

Taste becomes a competitive advantage you can’t fake with benchmarks.

4) “AGI” starts to mean “runs without you”

I don’t think 2026 gives us sci-fi AGI. Not the god-machine version.

But I do think the definition shifts toward autonomy.

Right now, most models run in short bursts: you prompt, they respond, you correct, repeat. The 2026 jump looks like agents that keep going. You give them a goal on Monday and they grind through it, step by step, fixing their own mistakes and asking for help only when they genuinely need it. You check in Friday and you’re looking at a real trail of decisions and outputs, not a single blob of text.

The hard problem isn’t “make it smarter.” It’s “make it reliable over time.” Long-horizon work, memory, tool use, permissions, safety, audit trails. Agency is where the real engineering pain is.

5) The trust problem gets loud

This part is less fun, but we’re not avoiding it.

As video generation gets harder to distinguish from reality, trust becomes the scarce resource. And it won’t stay confined to “internet weirdness.” It will leak into business, legal disputes, media, and politics.

Deepfakes are already annoying. In 2026 they become operationally dangerous.

I expect a wave of friction: stronger verification tools, watermarking standards, policy fights, and probably new rules around labeling. Whether regulation works is another question. But the pressure will be real, especially during election cycles and major news events.

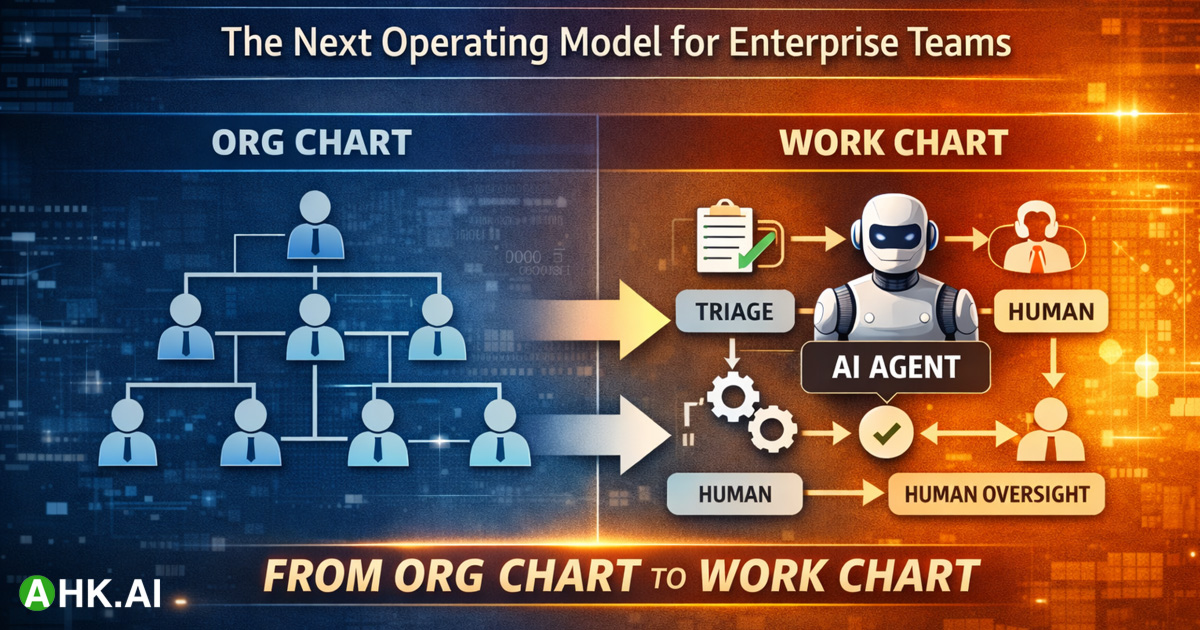

Where this leaves teams in 2026

There’s a fork in the road, but it’s not “humans vs AI.” It’s “manual-first software vs agent-first software.”

If you’re building products, you don’t need to throw everything out. You do need to start thinking in permissions, workflows, auditability, and agent-driven UX.

If you’re an engineer, the advice is blunt: learn to work with agents the way you learned to work with frameworks. The heavy lifting is moving. Your value shifts to architecture, constraints, verification, and taste.

The people who adapt won’t just move faster. They’ll build different kinds of software.

Want to explore what agent-native architecture looks like in practice? Book a Strategy Call with the AHK.AI team.